The Mystery of the Nasca Lines © Tony Morrison 1987 |

Chapter

1 — A Desert Mystery |

he Nasca valley has been inhabited for over two thousand years and traces of the ancient people can be found everywhere. Beside the Pacific Ocean just fifty miles to the west, immense heaps of shells stand as testament to rich harvests gathered by a long-forgotten fisherfolk. Close to Nasca the remains of pyramids, built from tens of thousands of mud bricks, are surrounded by a similarly indefinite number of graves. Over the years most of them have been opened and looted, but in 1926 there was much to find. So late one afternoon two archaeologists set out to climb a hill behind their camp near the cemetery at La Calera along the road south. The hill stands close to the valley edge, about thirty minutes of dusty walking from the centre of town. Alfred Kroeber, an American, and Toribio Mejia, a rising Peruvian scholar, scrambled across rocky slopes to find a lookout. The explorers needed to take advantage of the low angled sunlight just before dusk which gives form to even the subtlest features. Tumbledown remnants of dwellings, fortifications or ancient roads stand out clearly from the desert surface in such conditions and Kroeber and Mejía anticipated new discoveries. As they gazed down from the hilltop they saw curious furrows, or long straight depressions in the stony ‘pampa’ or level desert. Which of the two men first made the discovery may never be known and it has gone down in Nasca history with the same sort of question as ‘Who stood first on the summit of Everest .Hillary or Tenzing?’ In the case of the Nasca ‘lines’ both Kroeber and Mejía made notes of their impressions. Kroeber put his comments in one of his field diaries for the 1926, which he discussed with the great American scholar, Professor John Rowe. In response to Rowe’s question about his Nasca records, Kroeber said ‘My excavation notes are not very good’. John Rowe later added ‘They weren’t, but I saw his drawing of the lines’. Mejía

also made notes which eventually were published some fourteen years later. The alternative, and much more common are simple surface channels, which in Peru are as much part of the desert scene as thorn bushes and dunes. No wonder that the lines at La Calera were not immediately exciting to Kroeber and Mejía. There the matter could have rested had it not been for the lasting and exceptional devotion of Maria Reiche. Maria Reiche Maria

Reiche was born in May 1903 in the historic city of Dresden, the German centre

of art and culture known as the ‘Florence of the Elbe’. Maria’s father, Max Felix,

was a

They would walk together, often silently, in the woods of Saxony, each with their thoughts. She could have been set for a pampered life surrounded with the trappings of a classical education. She was eight in 1911 when the first performance of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier was given in Dresden, and the family thrived on music and the theatre, indeed Shakespeare remains one of Maria’s greatest pleasures. She also mastered English and French which she still speaks with fluency. Looking

back to her formative years of family and student days, Maria once said that her

spirit of adventure must have been touched with a personal rebellion. Behind all

her successes her sister Renate made the running. When

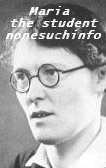

in 1926 the Nasca lines were first discovered, Maria Reiche was twenty-three and

a student of mathematics at Hamburg University. It was her love of children which drew her attention to an advertisement in a Hamburg newspaper which offered the post of governess in the home of the German Consul in Cusco, a Peruvian mountain city, once the fine Inca capital. Her application was accepted and without a second thought she set out alone on a five week sea journey to the southern Peruvian port of Mollendo. Maria has always insisted she was not fleeing the attentions of some student Romeo, though she has often remarked on her thoughts of marriage in those early days, saying how she felt love many times but ‘I never considered marrying a German; for me I wanted to make a one hundred per cent successful marriage if I made one at all’. Her instinct was leading her and she has never had any regrets. Part of Maria’s interest in South America was her budding enthusiasm for astronomy and she knew the work of the German astronomer Rolf Müller. In 1929 he published in Potsdam details of how certain Inca buildings in Cuzco had been built to face the rising sun at the important June solstice of the Inca calendar. The sun on this mid-winter day shone on a golden shrine in the Coriancancha or sun temple, the most sacred in all the Inca Empire. She also knew that the Incas held a special festival, the ‘Inti raymi’, in honour of the sun: it was a time of special dances when sacrifices were offered on the principal hills.

Maria has always said that she believes her days in Peru were predestined. ‘It is difficult to explain but you know when it happens. For me, Cuzco was simply the first step’. She once enlarged on her idea, saying how Cuzco and all Peru had greeted her like a ‘quadruple rainbow’; she never felt homesick for Germany except on her infrequent return visits. She settled quickly into her new life, caring for seven year old Erhard and the delightful four year old Hilda, the children of Herr Tabel and his wife. Herr Tabel, besides being the German Consul, was also, perhaps not surprisingly, director of the Cuzco brewery. Although the Inca foundation of Cuzco dates from AD 1200, at which time many of Europe’s cathedrals were already old, the open squares and narrow streets possess the qualities of a time capsule. All the sights, sounds and smells of this city transport a visitor back into the Middle Ages in reasonable comfort. Spanish colonial or younger buildings are supported on foundations of fine Inca stonework. Quechua Indians, the descendants of Inca dominated families, plod narrow streets bent as if genetically crushed by Spanish conquerors, though more probably by a legacy of heavy burdens. Maria Reiche looked on this scene and was fascinated by the customs of people who are at times barely a few steps removed from their ancestry. But as a governess she had little time to pursue her personal ambitions. Fortunately, the thing she enjoyed most of all in her work were long walks or outings in the children’s company. They were taken by Herr Tabel’s chauffeur to places in the mountains like Tambo Machay, the remains of an Inca hunting lodge. There, amongst springs and fountains built by the Inca Yupanqui, Maria and the children set out their picnic on a hillside carpeted with tiny yellow flowers, relatives of the European daisy. Of

the many facets of the new world around her, Maria began to understand the ways

of the Indians and their belief in ancient gods. The Spanish invaders had stamped

on the old customs and tried, though not always successfully, to superimpose a

catholicism which was seen by Maria through the eyes of the strictly conventional

Cuzco families. Exceptions were common as she discovered once she had found where

to look. Particularly fascinating to Maria, who already kept to a strictly frugal

diet, was the Indian reliance on herb medicines and a curious mixture of ‘magic’

and natural substances used for healing. She learnt, too, of the Indians’ understanding

of spirits and omens for healing. She learnt, too, of the Indians’ understanding

of spirits and omens both good and evil. Everything she had been accustomed to

had little relevance in the Indian world around her. At times her life could have

been a fantasy, beyond normal appreciation. It was after one of her jaunts into the Andean countryside that Maria found a splinter deep under the nail of a finger on her left hand. A severe infection followed and at the insistence of her employer she braved a Cuzco hospital and surgery for the removal of the tip of the finger. One of her old friends later remembered how Maria described the remarkable vision she experienced while her own body and, floating out of the window, had seen ‘all of Cuzco spread out below’. As she came out of the anaesthetic she realised she was returning to her own body. But her job was not to last. Maria and the Tabels never saw eye to eye. Although the children were her joy and she loved them dearly, when eventually they distanced themselves from their parents her contract was quickly terminated. The year was 1934 and she found herself bundled on a train with her luggage bound once again for Mollendo, where her ex-employer ensured she boarded a ship bound for Lima and onwards to Germany. Maria, however, was determined to stay in Peru. A friend in Lima When the ship berthed at Callao, the port for Lima, she was told her papers were not in order and was refused permission to go ashore. Here again, Maria believes that predestination played a part: during the voyage she had made friends with a lady who not only had the right connections but also tempted her to open a kindergarten in Peru. Maria accepted the challenge and immediately all the formalities were waived. She spent much of the next few months in Ancón, a small coastal resort surrounded by desert and about twenty-five miles north of Lima. It was a pretty town of palms and large avenues of South American pine trees and Maria spent much of her time wandering amongst the desert hills where ‘There is nothing but sand, nothing alive, no plants, no birds, no sound nothing but an immense silence and solitude. It gives you quite a peculiar feeling’. Ancón, a favourite resort with Lima society, was connected to the capital by railway which was always busy at weekends. Its climate, as Maria remembers, is somewhat drier than that of Lima, which in winter suffers heavy mist, or drizzle which the locals call ‘garúa’, and she noticed how many seabirds fed on the richness of the cold Peruvian current which itself influences the climate and helps create the extraordinary desert. ‘And the quantity of waterfowl! The pelicans are rather confident and come near the shore. By swimming one can get quite near to them’. She noticed how the pelicans ‘do not dive like ducks they have to rise a little bit out of the water and then, drawn by the weight of their heavy beaks, dip into the water like stones. With so many birds, it is a continual rising and falling and a very animated play as they move about near the shore’. The kindergarten started and almost as quickly closed, and once again Maria found herself without a job or permission to stay in Peru. She freelanced for a short while and then, in 1936, returned to Germany to stay with her mother in Hamburg. The

visit was short, Maria lectured briefly on her travels at the Völkerkunde

Museum, and then at a clinic in Halle, where Renate her sister was working. By

1937, less than a year since leaving Peru, Maria was once more on a ship bound

for South America and Lima. ‘Here I am, once more back in Gamarra Street’. Maria was living in a small rented apartment close to the centre of the city and giving lessons in mathematics and gymnastics three times a week at the English school. Once more she found that she developed a strong rapport with the children and this time it ensured her job. As she made friends in the pre-war Lima, Maria found herself drawn more and more into intellectual and cultural circles. By 1938 she was working in the National Museum, translating German scientific and technical journals. Another part of her work was the supervision of the restoration and repair of the beautiful cloths which wrapped the bodies of ancient Peruvians buried some two thousand years ago. These mummy wrappings are among the most exquisite works of art to have survived from pre-Columbian America, some of the most famous having been discovered in simple tombs beneath the sands of Paracas, a desert peninsular roughly half way between Lima and Nasca. Paracas - a discovery The Paracas site was excavated by the Peruvian master of archaeology Julio C Tello and Toribio Mejía, Tello’s principal collaborator when the work began in 1925. Two forms of burial were discovered and one, at Paracas-Necropolis which was found by Mejía in 1927, revealed 429 mummy bundles. The naked body was seated in a wicker basket and swathed in fine cloths. Between the layers of cloth, the decorated ponchos and shawls, the mummy was packed with all manner of goods for the spirit to take to the afterworld. Ornaments of gold, pottery, weapons, food and even pet animals were found with the ‘fardos’ as the bundles are called. Some of the largest were almost five feet high and took two men to lift them. The excavations continued until 1930, during which time Tello and Mejía discovered that some of the perfectly preserved mummies were wrapped in embroidered cloths of unrivalled quality. Some of the wrappings made from hand-spun wild cotton were as much as thirteen feet wide and up to eighty-four feet long. The embroidered designs in cotton coloured with natural dyes have the form of magico-religious characters, feline demons, warriors carrying trophy heads and an assortment of deities still being renamed and classified. Such was the scale of the ‘find’ at Paracas that, even now, many of the smaller bundles have remained unopened in the storerooms of Peruvian museums. Others, it seems, have just simply disappeared; not an uncommon occurrence in the world of high value ancient art. Maria’s work for Tello provided her with a small income and valuable experience which, even at the beginning of her new life, she is remembered as saying was ‘enormously interesting’. Though Nasca and its strange markings had yet to make its mark on her, the mystery that eventually took over her life was getting closer. At this time archaeologists were beginning to compare the Paracas-Necropolis designs with those found in burial grounds at Nasca and the intervening valley of Ica. Then, in the 1930s, flights across the desert become commonplace and pilots started to report lines from other parts.

Each spur of the mountains is embellished with a long thin triangular clearing. In the early days these clearings and the lines leading to them were the most noticeable features. But as pilots flew from Palpa southward to Nasca, a distance of about forty miles, they realised that the desert was covered with all manner of geometric shapes. As the first aerial photographs were taken slowly the lines became known. The British ethnographer and archaeologist, Geoffrey Bushnell, flew over the lines in 1939 and fifteen years later, as Curator of the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, he said ‘Whatever the explanation, the setting out and execution of these perfectly straight lines and other figures must have required a great deal of skill and not a little disciplined labour’. But

in 1939 the fact was that the lines were a curiosity. Though the shapes and straight

lines were being classified by Toribio Mejía, urged on by Tello, they were

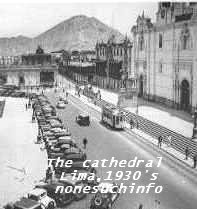

very much an afterthought to his work on the irrigation puquios. The markings drawn by Toribio Mejia Xesppe 1939 As the date of the Congress approached Maria happened to make friends with Amy Meredith, an English lady some twelve years older. Amy, who owned a small teashop in the centre of the city, had both charm and a bubbly personality. Her reputation among the foreign community for generosity set her apart. ‘She was a typical English rose’, a long time resident once said, ‘and she had a strong, serious social awareness which at the time seemed quite unusual’. Peru in the 1930s was a country of rich landowners and a large Indian labour force, and Amy’s social conscience could not fail to be noticed when, as her business developed, she introduced a system of profit sharing among the employees, giving them each a monthly dividend. Maria and Amy became great companions, spending much time together and always enlarging their circle of friends. Amy gave famous tea parties, sometimes with as many as forty guests who, in the social style of the day, stood in groups to drink tea and eat light biscuits. This kind of entertaining was very much suited to Maria’s own frugal style and her friendship with Amy grew to be long and lasting. They travelled together on camping excursions near Lima, sometimes returning to the sea which Maria always enjoyed. Often Maria helped Amy in her teashop, which had become a well-known gathering place for transient foreigners, for the teashop, in a narrow open walk or pasaje near the Plaza de Armas, the main square, was well placed to catch travellers, sightseers and shoppers. The neo-Baroque Presidential Palace built in 1938 was within sight of the door and the Desamparados railway station for the highest line in the world was five minutes walk away. Across the plaza to the right stood the cathedral with the 464 year old remains of Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of Peru, lying shrivelled and dry as husk in a glass casket. Any traveller, even those in town for the day from visiting ships berthed in Callao, was bound to find Amy’s shop, so it was no surprise to find among the customers those academics who had stayed after the Congress. Paul Kosok - a man of vision Paul

Kosok, a well-built native New Yorker from the Long Island University, was just

one of many who called at the teashop where his enthusiasm caught the attention

of Maria and Amy. Most of his work was focused north of Lima where the remains of pyramids, fortresses, canals and settlements rest incongruously among sprawling fields of sugar cane. But Lima offered museums and libraries and Maria Reiche found herself once more employed as a translator, this time for Kosok. It was early in 1941 that he decided to travel to Nasca. Toribio Mejía ‘s account of the lines and the possibility that they were connected with irrigation was sufficient to persuade him. He arrived with Rose on the Nasca desert in June. For

reasons which are not clear Kosok decided to work on the desert pampas a few miles

to the south of Palpa. Possibly the very obvious cleared areas at Palpa were an

attraction, or it could have been because of the reports of truck drivers who

knew of some extremely long lines not far from the settlement of Llipata, a Paul Kosok turned to the first hill and found that it was the centre of a complex of lines. Some narrow, others more than ten feet wide. Some lines led to the crest of the hill, their form being clear as shallow U-shaped trenches. At the top, overlooking the desert, Kosok found piles of stones at the ends of the lines and a large area cleared of surface stones. The clearing followed the form of the hill though with a clearly defined trapezoid outline. The

conditions on the desert were not good. Kosok and his wife had to carry everything

they needed for the day’s work, including drinking water. But as they traced the

form of the trapezoid they realised that one end was embellished with a complex

design of scrolls and finger-like projections. The pattern was scraped in the

ground, though to a lesser depth than the main shape of the clearing. This was

the first of the designs to be discovered, and describing it Kosok could offer

no explanation: ‘What it portrays we do not know’. It was on the same visit that Kosok noticed the sun setting almost directly at the end of a line and understandably he was ‘Struck with the thought that the remains could have had some astronomical or calendrical connections’. These ideas were uppermost in his mind as he headed back to Lima and Amy’s teashop. Once more among interested friends he talked over his discoveries and ideas with Maria Reiche who was enthralled. Here was her subject: mathematics with astronomy, time, calendars and her new interest in archaeology all rolled into one. Kosok offered some small funds to Maria if she would continue the investigation after his return to the United States. She agreed. ‘Once more I knew it was my predestination at work’. The next stop involved more observations of the sun and Maria and Paul Kosok decided that she had to go to Nasca and see that year’s December solstice, the time when setting and rising sun reaches its extreme position on the north-south journey along the horizon. All the evidence up to that moment pointed, according to Kosok, to the lines being an ancient calendar. ‘It was’, he said, ‘the largest astronomy book in the world. CONTINUE TO CHAPTER TWO ..'THE LARGEST ASTRONOMY BOOK'

|

Both

impressions were almost casual, and neither Kroeber nor Mejia attached great significance

to the markings which they assumed were unprepossessing attempts to build irrigation

channnels. At the time of the discovery of the desert markings or ‘lines’, Mejía’s

interests lay more with the unusual subterranean water channels or puquios. These

man-made tunnels, running for long distances below the valley, resemble the qanats

of Iranian deserts and surprisingly are unknown in other parts of Peru. Gravity

wells, as these tunnels are known, were built to tap the phreatic or ground water

below the watertable, so were a relatively sophisticated development.

Both

impressions were almost casual, and neither Kroeber nor Mejia attached great significance

to the markings which they assumed were unprepossessing attempts to build irrigation

channnels. At the time of the discovery of the desert markings or ‘lines’, Mejía’s

interests lay more with the unusual subterranean water channels or puquios. These

man-made tunnels, running for long distances below the valley, resemble the qanats

of Iranian deserts and surprisingly are unknown in other parts of Peru. Gravity

wells, as these tunnels are known, were built to tap the phreatic or ground water

below the watertable, so were a relatively sophisticated development. judge and

her mother Elizabeth, or Elli as she was fondly called, had studied in both Hamburg

and Edinburgh.In 1906 Maria’s younger sister Renate was born, and three years

later their brother Franz.

judge and

her mother Elizabeth, or Elli as she was fondly called, had studied in both Hamburg

and Edinburgh.In 1906 Maria’s younger sister Renate was born, and three years

later their brother Franz. The

Reiche home was a fine house in the old city, with vines and flowers filling the

garden, but life for the three young children was strict, even cold at times.

As Maria grew, however, she came to understand her father.

The

Reiche home was a fine house in the old city, with vines and flowers filling the

garden, but life for the three young children was strict, even cold at times.

As Maria grew, however, she came to understand her father.  Renate

excelled at sports and pushed Maria to try harder, and it was Renate who persuaded

her to accept with resolve the myopia which has dominated her life. But above

all Maria’s determined inquisitiveness began to surface: she was a dedicated mathematician

and thrived on problems of logic.

Renate

excelled at sports and pushed Maria to try harder, and it was Renate who persuaded

her to accept with resolve the myopia which has dominated her life. But above

all Maria’s determined inquisitiveness began to surface: she was a dedicated mathematician

and thrived on problems of logic. Like

many of her friends she was aware of the political maelstrom enveloping post-war

Germany where Adolf Hitler had just published Mein Kamp. Maria on remembering

these times, insists she was not a political animal. ‘In fact I felt disgusted

at the thought of all the hatred being generated and I wanted to distance myself’.

Yet like so many young people of the day, perhaps out of curiosity, Maria found

herself drawn into discussions and noisy student meetings. Being athletic, enjoying

swimming, diving and other sports, in the eyes of some she could be seen as the

archetypal Hitler Youth. But while the National Socialists swept forward in the

polls, eventually commanding six and a half million votes in 1932, Maria became

all the more determined to leave her country.

Like

many of her friends she was aware of the political maelstrom enveloping post-war

Germany where Adolf Hitler had just published Mein Kamp. Maria on remembering

these times, insists she was not a political animal. ‘In fact I felt disgusted

at the thought of all the hatred being generated and I wanted to distance myself’.

Yet like so many young people of the day, perhaps out of curiosity, Maria found

herself drawn into discussions and noisy student meetings. Being athletic, enjoying

swimming, diving and other sports, in the eyes of some she could be seen as the

archetypal Hitler Youth. But while the National Socialists swept forward in the

polls, eventually commanding six and a half million votes in 1932, Maria became

all the more determined to leave her country. Much

of this rich symbolism was still surviving when Maria reached South America so

there was more than enough to see and learn to keep her interest buoyed up. Her

thoughts were never more positive than during the long train journey she made

across the mountains from Mollendo to Cuzco. The track climbs from the sea through

a gaunt landscape of burnished rock bearing hardly a scrap of life. Breaks in

sterility come only when the train winds into deep valleys lying at the foot of

the gigantic volcanoes, beyond which it climbs tortuously to fifteen thousand

feet high passes, hot springs and snow-capped peaks.

Much

of this rich symbolism was still surviving when Maria reached South America so

there was more than enough to see and learn to keep her interest buoyed up. Her

thoughts were never more positive than during the long train journey she made

across the mountains from Mollendo to Cuzco. The track climbs from the sea through

a gaunt landscape of burnished rock bearing hardly a scrap of life. Breaks in

sterility come only when the train winds into deep valleys lying at the foot of

the gigantic volcanoes, beyond which it climbs tortuously to fifteen thousand

feet high passes, hot springs and snow-capped peaks.

One

pioneer airline started by a lanky American, Elmer J ‘Slim’ Faucett, had stopping

places on its route southward to Arequipa. The aircraft included specially adapted

machines known in Peru as ‘Stinson-Faucetts’ and these had the capability of taking

on some of the highest mountain passes. Stinson pilots on the Arequipa journey

had to reach over 9,000 feet and almost 4,000 between Ica and Nasca. Looking down

to rugged Andean foothills, pilots passed over the range of Santa Cruz, now pierced

by a road tunnel, before they saw the first markings on the greyish-red desert

near Palpa.

One

pioneer airline started by a lanky American, Elmer J ‘Slim’ Faucett, had stopping

places on its route southward to Arequipa. The aircraft included specially adapted

machines known in Peru as ‘Stinson-Faucetts’ and these had the capability of taking

on some of the highest mountain passes. Stinson pilots on the Arequipa journey

had to reach over 9,000 feet and almost 4,000 between Ica and Nasca. Looking down

to rugged Andean foothills, pilots passed over the range of Santa Cruz, now pierced

by a road tunnel, before they saw the first markings on the greyish-red desert

near Palpa. Mejía had made a special trip to Nasca to draw some of the lines and planned

to annouce his work on both projects at an International Congress in Lima to which

experts from all over the world had been invited. While Maria was working with

Tello he had introduced her to many archaeologists who were preparing their work

for the Congress. She delved deeply into the understanding of ancient Peru and

developed a liking for the ways of the Peruvians. Friends who remember her during

those days say they have no doubts about her desire or her ambition to stay and

research. ‘The Peruvian earth has put its spell on me’, she said at the

time.

Mejía had made a special trip to Nasca to draw some of the lines and planned

to annouce his work on both projects at an International Congress in Lima to which

experts from all over the world had been invited. While Maria was working with

Tello he had introduced her to many archaeologists who were preparing their work

for the Congress. She delved deeply into the understanding of ancient Peru and

developed a liking for the ways of the Peruvians. Friends who remember her during

those days say they have no doubts about her desire or her ambition to stay and

research. ‘The Peruvian earth has put its spell on me’, she said at the

time. The ebullient Kosok was a man of many talents. He excelled at history, he dabbled

expertly in archaeology, he was a talented musician and conductor – so much so

that his real métier should have been music. One of his colleagues remembers

him as a ‘great eccentric who thrived on work’. Twice married, Kosok travelled

to Peru in 1939 with his second wife Rose Wyler. He had joined Long Island University

ten years earlier as an instructor specialising in history. The trip to Peru was

intentionally brief; more of a preliminary survey of the ground he intended to

cover in a proposed study of early irrigation methods. Kosok then returned to

the United States to present his work to a congress in Washington in 1904. Later

the same year he took a year’s leave of absence from the university and returned

to Peru with Rose.

The ebullient Kosok was a man of many talents. He excelled at history, he dabbled

expertly in archaeology, he was a talented musician and conductor – so much so

that his real métier should have been music. One of his colleagues remembers

him as a ‘great eccentric who thrived on work’. Twice married, Kosok travelled

to Peru in 1939 with his second wife Rose Wyler. He had joined Long Island University

ten years earlier as an instructor specialising in history. The trip to Peru was

intentionally brief; more of a preliminary survey of the ground he intended to

cover in a proposed study of early irrigation methods. Kosok then returned to

the United States to present his work to a congress in Washington in 1904. Later

the same year he took a year’s leave of absence from the university and returned

to Peru with Rose. stop

along the way south. One traveller who knew this place from as far back as 1929

was Duncan Masson, a young Scot who was working on the nearby farm of Las Mercedes.

stop

along the way south. One traveller who knew this place from as far back as 1929

was Duncan Masson, a young Scot who was working on the nearby farm of Las Mercedes. Masson had passed through the desert crossing the lines, and some years before

he died he recalled the experience: ‘As we drove over the pampa we saw these

furrows to the left and right of the track. They were obvious… you couldn’t miss

them. We thought they were old roads’. It was to this place that Kosok headed

first and, sure enough, to the left of the road he found a perfectly straight

line leading to a hill almost two miles away. On the other side of the road the

line continued across the desert to the foot of another range.

Masson had passed through the desert crossing the lines, and some years before

he died he recalled the experience: ‘As we drove over the pampa we saw these

furrows to the left and right of the track. They were obvious… you couldn’t miss

them. We thought they were old roads’. It was to this place that Kosok headed

first and, sure enough, to the left of the road he found a perfectly straight

line leading to a hill almost two miles away. On the other side of the road the

line continued across the desert to the foot of another range.