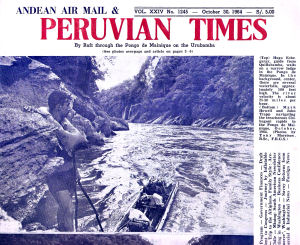

| By Mark Howell One

of the most difficult questions to answer, about the journey Tony Morrison and

I made down the Vilcanota and Urubamba rivers * — from Urcos to Atalaya is

why we did it. "Well " one starts, " It was like this..."

And then one tends to find oneself at a loss for any succinct and satisfactory

way of going on. Broadly, it was an attempt to find out whether it was possible

to travel by boat from a source of the Amazon down to one of the generally accepted

upper limits of navigation, and if so to film the descent. Another dubious distinction

we could claim, would be that we were the first people to navigate the Pongo

de Mainique in a rubber boat. Probably one of the best reasons, though is

curiosity; to visit the almost unknown areas of the valley below the Pongo is

possible only by river. *

See the Peruvian Times of Feb.22, 1963 for reference to other descents of the

Urubamba. The Urubamba above Machu Picchu is generally referred to as the Vilcanota

although there is no general agreement as to where the river changes its name.

[Peruvian Times editor] Mark,

Tony John [Johannes] and Hugo returned to Quillabamba after a two week walk in

the Vilcabamba range to cover a story about a Lost Inca City. Last

Stage on the Urubamba Our return journey took four days and 2 weeks

after we had set out from Quillabamba we were embarking on the last and, reputedly,

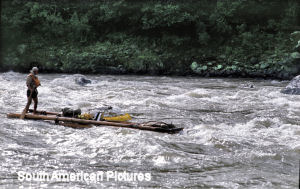

the most dangerous stage of our descent of the Urubamba. We had bought a balsa

raft, to be captained by Hugo from which Tony could film the progress of the dinghy

in close-up. Whirlpools

Although

the river appeared to have changed only in size, closer acquaintance made possible

by a rubber boat, showed more disturbing charactersistics. The whirlpools previously

small enough to 'skate' over , were now large enough to hold us for minutes on

end. They were only avoidable by staying in the main current on the bends where

five and six foot waves converged from all directions and permanent spray threatened

to fill the boat. At first we were fairly complacent — "well with all

this air in the boat we can't sink" — an opinion we modified when we

discovered before long that two violently converging currents could surge over

our one foot freeboard, and float off with our film in less time than it takes

to tell. Sometimes it was possible, by paddling frantically, to avoid an obstacle

spotted two hundred yards downstream, but more often it was only possible to utter

a heartfelt prayer and emerge from a welter of six foot waves resolving to stop

this idiocy immediately. Whereas higher up almost every rock or obstruction seemed

to have protective cushions of water around it, below Quillabamba it was not unusual

to see the main current dive below an undercut cliff and emerge from the depths

in a boiling upsurge many yards downstream. In the course of two days our paddling

muscles developed impressively; and our general tacit consensus of opinion, that

this was a river to treat with immense respect. Unnerving recollections of the

number of unfortunates this river had drowned returned to distract us from time

to time. Seven

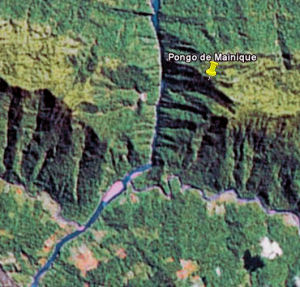

Great Rapids The

final descent of the Urubamba to the Pongo de Mainique is through a series of

seven great rapids, like the treads of a stairway. The balsa raft went through

the first with Hugo expertly threading between the spray shrouded rock. It seemed

to us in the rear boat to be moving at a frightening speed. Tony standing on the

front and holding the movie camera above his head, was submerged to his chest

with every wave. Then it was our turn. We swept through the first rapid shipping

only a few gallons, and shaped up for the second. It was not until we were twenty

yards from it that we realised the significance of a high standing wave blocking

half the width of the river. A huge boulder the top of which was perhaps four

or five feet below the surface was causing a build-up of water— we had seen

several much smaller ones upsteam. The danger was not in the wave but the great

hole in the water behind the rock, which was four or five times as deep as the

height of the wave. We paddled as we had never had before, but it was hopeless.

As we swept up to the crest of the wave I had a momentary glimpse of a hole eight

or nine feet deep and then the boat was tossed high into the air and we were ejected

from it like stones from a catapult. Survival

Afterwards

Hugo told us that the longest a strong swimmer can expect to survive in one of

these rapids is about two minutes. As John and I were wearing jackets, trousers

and shoes it was a miracle we lasted that long. Somehow John managed to grasp

one of the dinghy's life lines, but I was swept away from it and had I not managed

to seize a piece of basla wood which had been thrown out of the dinghy with us,

I should have drowned in the rapid. As it was I was too exhausted by the violence

of the water to be able to swim with any power when I was into the calm but swift

section 200 yards downstream. Fortunately, Hugo was able to manouevre the balsa

close enough to me to dive in wearing a life jacket, and drag me into the bank.

We reached it only ten yards above the next rapid which would have drowned both

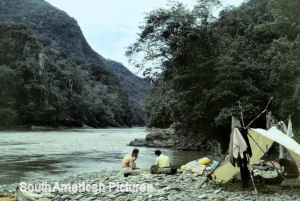

of us. Half

an hour later when I had recovered enough strength to walk, we found the others

some 500 yards downsteam where John had managed to beach the dinghy with an oar

he found jammed underneath it. Most of our valuable equipment had been tied into

the boat, the cameras and film had been wrapped in plastic sheeting and had not

suffered, but our tape recorder, a pair of shoes and a jacket had been washed

away. However the gratifying thing was that neither John nor I had been. The

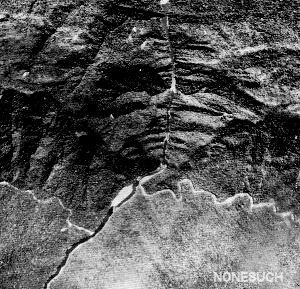

Pongo de Mainique In

an hour we were ready to continue. My own attitude was one of complete resignation;

having barely escaped drowning, and still completely exhausted, I should perhaps

have resisted the suggestion to continue, at least for a while. But when, ten

minutes later I saw the mouth of the Pongo come in sight I summoned a surprising

amount of energy for evasive paddling. The water boiled and disappeared into a

high, dark, forbidding cut in the hills; I recall a vague impression of a confused

white water slope and then we were slipping along on an absolutely calm surface,

very fast between high grey walls; we had entered the Pongo of awful repute. This

was the climax of our whole expedition; the Pongo had never been filmed and only

rarely and inadequately photographed. Usually, merely passing through it had been

reckoned an adequate enough achievement. While keeping a wary ear cocked for the

sound of breaking water downstream, Tony filmed the dinghy gliding past the sheer

grey cliffs iof the canyon. Waterfalls cascaded down in graceful veils. Halfway

through the Pongo, we had been warned, was a dangerous rapid with two whirlpools,

but we bounced through this hardly shipping a drop. The walls on either side of

us climbed higher, probably 600 or 700 feet, and the sky diminished to a narrow

strip. Dense, damp, vegetation covered the upper levels of the cliffs, absorbing

all sound except the incessant drip of water. Twenty

minutes after entering it, we passed through the jaws of the Pongo, two high cliffs

jutting into the river, narrowing the gap by more than half. Hugo pointed up and

said " 'Once there was an Inca bridge across there ". John and

I shouted our disbelief and he shrugged his shoulders eloquently. Then within

minutes the river was ten times as wide, slow and widing. We paddled unhurriedly

across to a long low playa [beach] which would serve for our first night's

camp on this new languid river, glad that we had survived but sorry too, in a

way that for the next 200 miles would be just a leisurely unwinding lowland river. A

piece of advice I feel bound to give to anyone wanting to navigate the lower Urubamba,

is that to attempt it without a guide would be suicidally dangerous. Although

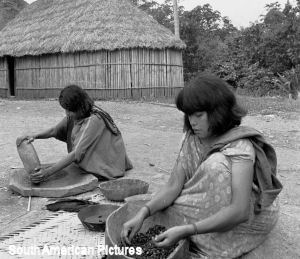

we were unable to obtain any Machiguenga guides, Hugo had been through the Pongo

several times, although not on a balsa, and he was an experienced riverman. Had

it not been for him one of us at least would probably have drowned. And the already

impresssive score of fatalities the Pongo already has to its credit shows that

our experience was nothing out of the ordinary. The

Boat used by the Urubamba expedition was a 9-foot Avon Redcrest

manufactured in various sizes by the Avon Rubber Co, Melksham, Wiltshire, England.

[now Avon plc] Hugo Echegueray the guide on the Urubamba expedition was so impressed

by the handling and other charachteristics in the dangerous conditions of the

Urubamba that he is planning to set up an agency for importing the craft. Publisher's

note referring to Howell's book ' Journey Through a Forgotten Empire'

" They saw the 'Lines of Nazca', the gigantic calculations astronomers

drew on the featureless desert thousand of years ago; they spent some days on

the feudal estate of the millionaire Suares; they had the amazing luck to find

the unique Chipaya community, poignant living remnant of pre-Inca time two days

before 'civilisation' in the shape of dried milk and electricity arrived by courtesy

of US AID; and finally in San Antonio de Lipes, a high Andes ghost town, they

stumbled upon the crumbling remains of a vast and richly appointed cathedral." Now

to bring the story up-to date... - 1967

' Steps to a Fortune' a book by Mark Howell and Tony Morrison,

Geoffrey Bles, London. It includes an account of a meeting with Fidel Pereira

the patriarch of the lower Urubamba and an account of the journey through the

Pongo.

- This

region of the eastern Andes is noted for its great bio-diversity It is a meeting

place of species from the slopes of the mountains and Amazon lowlands. Also their

is a movement of species both plant and animal north and south using the mountains

as a pathway. The Pongo like a gateway offers free movement especially for birds

and insects.

- Over

the past fifty years the road down the valley from Quillabamba has been extended

- bit by bit more or less as settlements have required. In the 1960's only the

remnant of an old trail led to the Pongo and beyond. The trail was made at the

end of the 19th century when this area was part of a much larger 'Rubber Empire'

where natural rubber was collected and exported via the Amazon river.

- In

the 1980's Tony has returned a couple of times by air overflights and to the even

more remote Isthmus of Fitzcarrald while following the story of Lizzie Hessel

an English woman who travelled to rivers just below the Pongo with her husband

in 1896. They were employees of Carlos Fermin Fitzcarrald an entrepeneur intent

on making a fortune in the Rubber Boom / Lizzie- The Amazon Adventures of a

Victorian Lady, Tony Morrison, Ann Brown and Anne Rose, BBC Books 1985

- In

recent years the lower Urubamba - above and through the Pongo has become a whitewater

rafting destination.

- The

Pongo has featured in several films, notably in 'Fitcarraldo' 1982 written and

directed by Werner Hertzog; A BBC travel series Full Circle' 1997 with Monty Python

actor, Michael Palin; and documentaries.

- Modern

accounts often say say an Inca bridge exists across the Pongo - they must be incorrect

as the bridge was was not there in 1964. If it's there now it's certainly not

Inca.

Early

accounts 1916

The Andes of Southern Peru Isaiah Bowman / American Geographical Society /

Henry Holt and Company, New York. Yale Peruvian Expedition 1911, Hiram Bingham,

credited with discovering Machu Picchu was Director of the expedition. 1932

West Coast Leader [Predecessor of the Peruvian Times] July 26th 1932, A report

of the death of Professor J. W Gregory. 1953

Rafting the Urubamba Malcolm K. Burke a series of eight stories in the Peruvian

Times, Lima, February 3rd / March 19th 1956 - Malcolm Burke was a writer based

in Lima and he made raft journeys down the main Amazon tributaries. All reported

in the Peruvian Times. 1958

Quest for Paititi, Julian Tennant, Max Parrish , London [1954] 1961

The Cloud Forest, Peter Matthiessen, Viking, New York And

there may be others before 1964 - if so please send an e-mail to the editor -

see CONTACT INFO To

return to the top of this page

|

|

| The

text and most of the images are © Copyright |

| For

any commercial use please contact | | |

| THE

NONESUCH - FLOWER OF BRISTOL |

| AN

EMBLEM FOR ENTERPRISE | | |